I never dreamt about being in prison during my incarceration. Every once in a while, I dreamt that one or more of my friends (from inside) and I were hanging out at one of the places I missed and remembered — New York City, the Exeter campus, the recording studio. But to my recollection, I never had a dream that took place in prison. The most frequent destination in the dream state was the house in which I spent my adolescence, on Legion Street in Brownsville, Brooklyn.

Brownsville, with the help of the times (i.e. the proliferation of crack cocaine in every major city in the US during the mid-1980s), acquired an Enter-at-Your-Own-Risk reputation. The so-called luxuries that were afforded to drug dealers (cars, jewelry, and clothes) came with a price — the seemingly inexorable final destinations of prison and/or violent death.

I would lay awake in bed, numb to the gunfire just outside my window, counting the shots like sheep.

Notwithstanding the statistics (one in nine black men between the ages of 20 and 34 are currently incarcerated within the criminal-justice system), the promise and proximity of drug dealing is oftentimes too influential to be overcome by logic and intuition.

For as long as I could remember, being from the city was associated with an innate swagger, a defense mechanism built on skepticism and bravado. Keep your guard up! Don’t be nobody’s fool! That kind of thinking. The durability of youth in the 1980s in Brownsville and other similar places was replaced with a mentality that was as empowering as it was impossible to bear.

Brownsville! Never ran… never will.

Do-or-die Bed-Stuy.

Gangs were born and buried throughout Brooklyn and the other boroughs in the late 1960s and ‘70s. Back then, however, disputes were predominantly settled with fists. The wealth (or at least the illusion of wealth) that was created in the 1980s also brought with it a bloody, news-making urban warfare, where a worst-case scenario was not a night in a county jail cell and being admonished by an infirmary nurse for your involvement in a brawl. The violence that began to define the era was a game changer, one that required incredulous family members to “please identify the body.”

I remember sitting on my bedroom floor in our second-story apartment watching the evening news. The scenes of violence in Beirut (even in snowy black and white) were enough to leave a deep impression on my young psyche. How can people live there? I wondered. Why don’t they move? Later that night, I would lay awake in bed, numb to the gunfire just outside my window, counting the shots like sheep.

Indeed, some of my childhood friends became casualties of the violent times. Some of them left school during the years when school was not about critical analysis but rather learning by rote — the memorization of characters, dates, multiplication tables, etc. During those years, school was not particularly trying for me. My first day of classes at PS 183 was an event insofar as the homeroom teacher sent me to the principal’s office shortly into the morning session, just before lunch. I tripped into the office neither afraid nor arrogant — just confused. The secretary told me my mother had been notified and she was on the way.

“But I didn’t do anything,”I objected in earnest.

“Just have a seat,”she calmly advised.

The homeroom teacher came into the office shortly after my mother arrived.

Talking to them, but looking at me, my mother asked, “Is everything all right?”

“Ms. Forté,”the teacher began, “your son does not belong here.”

“Pardon?”said my mother.

“John is not challenged by our curriculum. We don’t have the programs to accommodate him. I suggest he be tested for a gifted program.”

The next afternoon I was a student at PS 327, considerably farther away than my former school, an eight-year-old second-grader in the 2GT Class — gifted and talented.

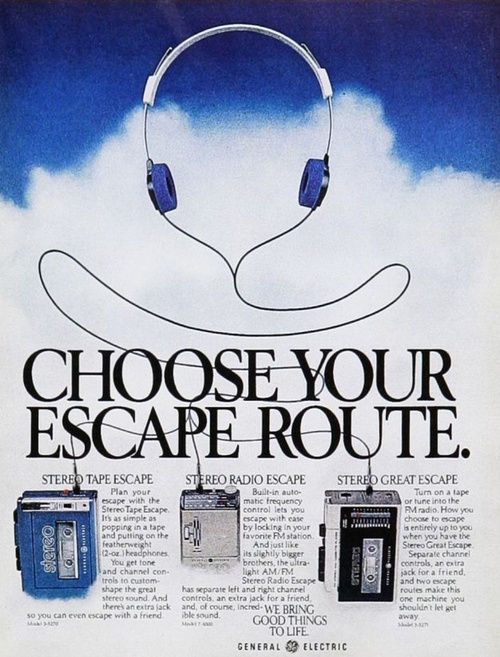

Before long, we were all affected by the sphere of influence drugs possessed. Someone close to you was using, dealing, or both. And as the realization of social class and the discrepancies therein began to permeate our consciousness and influence our judgment, the options for success seemed to simultaneously narrow before our very eyes. The pervading models of triumph were entertainers, athletes, and drug dealers. The ‘hood was not exempt from the profligacy of the times. Black and brown people on the lower rungs of the socio-economic ladder were not immune to the seduction of conspicuous consumption. Keeping up with the Joneses during that period became as en vogue as renouncing one’s earthly possessions in the era that preceded it. Even if (and sometimes especially if) that meant growing broke in the process of trying to look like a million bucks.

One didn’t have to see the drug users in the act of using to know they were using. I noticed the empty vials on the broken sidewalks and thought nothing much of it. For all of its issues, the community was like any other family — riddled with dysfunction, albeit fully functional and more than capable of thriving. There I was, traveling to and from school with my backpack filled with books and my tiny violin inside my tiny, black violin case. Occasionally, friends would make requests.

“Can you play Planet Rock?”

“Nope,”I’d say laughing, “But I know Vivaldi’s Four Seasons.”Autumn was, and remains, my favorite season. After screeching through my cultured set list, I would go upstairs, woodshed any unfamiliar pieces and rehearse them for school the next day. I kept myself occupied with more than just music — I drew, I rode my bike, and I played on the Bantam League baseball team in Prospect Park.

Though for all of the good times we had as kids in Brownsville, we spoke often and openly of getting out, what we would do if we had the chance, and so on. We knew that for all our laughter, family, and togetherness there was something better. I eventually did make my way out. My love affair with academia kickstarted that process, and at the age of 14 I left Brooklyn for Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire.

More than once during my years at Exeter, when I recounted the graphic sights and chilling sounds of Brownsville to friends who had neither family nor business in such a community, they would ask, “How could you have lived there? Why didn’t you move?” Touché.

Despite my awareness of the daunting statistics and the gifts I had been given, I wound up in prison — a young, black man from a loving family, educated, and who should have known better. I fell. Hard.

Today, in my attempts at regaining my footing — reconnecting with friends and family, learning the new technologies which have arisen in my absence, helping to deter young people from making the same mistakes that led to my incarceration — I recognize the blessing of reflection and the responsibility of voice. And after all of the searching, something deep within keeps returning me to Brownsville, Brooklyn, where it all began.

The Alchemist, The Prophet, The Little Prince, these tomes all tell the stories of sojourns away from, and back to, where we began. I read these books more than once over the years and each time I encountered something new. I have yet to have a dream about being in prison. I hope I never do. I have had my fill. Brownsville? Well, that is a different matter altogether.

I learned to get with my hands

To do better

Like dude, “You knew better!”

But life is fast moving

How quick could you get up?Excerpt from “Homecoming”

John Forté featuring Talib Kweli